Something has been happening with physician medical visits. Maybe I’m just noticing it because my doctor quit and I had to find a new one, which put me on a treadmill of repeat appointments—because, as my new physician told me, she was out of time for our visit. But here’s the rub: Apart from seasonal allergies, there is nothing wrong with me.

I am, thankfully, extraordinarily healthy. I have no hypertension, diabetes, cardiac issues or auto-immune diseases. My lipids are normal and my weight hasn’t changed since I was 21. The only meds I take are for allergies.

Yet so far, in this new medical relationship, I have had two primary care visits but no exam except for a quick check of my throat and ears, bunches of blood tests and a chest x-ray. After the first visit, my primary promised that the second appointment would give us enough time to deal with “all my issues.” Okay, there are none. But trying to play the catch-up game, I went with it. At that second visit, she virtually scolded me when she ran out of time again, because somehow, I had used all of it. Then she asked that I come back for a third visit for the exam.

At the second visit, she also referred me to a pulmonologist because my chest x-ray showed some fibrosis—possible old histoplasmosis—in my upper right lung. That was the same finding as previous tests, but she hadn’t read any of the documents and images I provided. So I went, but first I called that pulmonologist. I told the office about two sets of available images, which I knew the specialist could access. I wanted to make sure that the specialist reviewed those images so that they could be discussed and compared at the visit.

Guess what? The pulmonologist didn’t have time to do this in advance, and would I please schedule a second visit to review the images and all the additional (negative) blood tests.

Cost and Quality Implications of Clinician Visit Time

Physician practices have been purchased or consolidated over the last several years, while at the same the market has moved towards Value-Based Health Care. Practice consolidations have been guided largely by a strategy of leveraging better contracts with health plans and building a stronger patient base. Although many networks have been built with the future of financial risk and ACOs in mind, the incentives currently are still fee-for-service. As a result, visit volume is the key indicator for both growth and revenue.

Here’s why: Physician productivity standards expanded as physician practices were purchased or consolidated in the past few years. However, these metrics make it very clear that physicians are part of a revenue growth objective, as opposed to value. All the indicators drive towards more visits, more revenue, and more downstream services of both physicians and other practitioners.

Fee-for-service benchmarks have put pressure on physicians to produce as many visits as possible within a short time frame, and likewise to cut patient appointments into repeated appointments for revenue recurrence—as I apparently experienced first-hand.

How visits have increased, however—and what that means for quality and cost—is not well documented. In fact, the most interesting revelation from literature reviews is that we continue to measure larger statistics of growth and usage in health care, without measuring the value and trends of usage that may be physician-driven or consumer-driven.

The latest National Health Insurance Interview Survey reveals that a high percentage of people with health care coverage, across all age groups, access professionals at least one time per year, and most of those have repeat visits to physicians within six months. Even for consumers between 18 and 44, almost 60 percent had more than one visit to physicians within that time period. Whether those visits represent a trend of care that is divided by financial incentives and productivity standards into smaller chunks of time is unknown.

What is clear, however, is that an average physician visit time of 15-17 minutes is consistently measured. According to one observational study, the average length of an office visit for an elderly person was 15.7 minutes, with a maximum of 5 minutes spent on the longest topic. And, despite a huge growth in total visits, technological changes, advances in science, public discussion on the need for higher patient engagement and more discussion, the duration of the average office visit did not significantly change from 1993 through to 2010. This speaks not only to the pressure of productivity standards on physicians, but also to the need for a culture shift.

How Engaged Can Clinician and Patient Be In a 15-Minute Average Office Visit?

Every day I read censures by providers and politicians of patients who will not “comply” or “engage,” and how we need to cut excessive consumer spending on health care. But the reality is that we are blaming the patient for a system problem.

Can an office visit of 15 minutes allow for adequate time with a patient? We need to evaluate whether it can accommodate the activities recommended in both quality performance measures and in plans that insist the consumer take a stronger role in making decisions:

- Is 15 minutes enough time for setting patient goals, creating a long-term patient plan and determining patient preferences?

- Does 15 minutes allow for reviewing literature about the benefits and harms of recommended treatments?

- Does 15 minutes allow for enough conversation as well as examination of the patient?

- Is 15 minutes, in fact, enough time for exploring any ideas of promoting patient engagement or building a physician-patient partnership?

The Case for Different Measures of Physician Value

We live in a time when consumers are getting smart enough to demand participation in a system that has been failing them—and now wants to charge them more money for the privilege. At the same time, payers of health care and provider-based ACOs have increased the volume of physician extenders—nurse practitioners and case managers, among other roles—that are providing direct services to patients.

Unless physicians can produce the results of better outcomes and lower costs that a shared partnership with patients is intended to achieve, payers and other health care organizations will expand the use of these providers and minimize the role of the physician. Walgreens, Walmart, Costco and CVS are all capitalizing on the idea that physicians should only perform limited services that warrant their diagnostic and technical skills. In view of a looming physician shortage, it may be a necessity as well as better economics to rethink the roles that physicians must play in the health care spectrum.

Physicians may be unwittingly falling into a trap of providing high-cost hourly services that will be shifted to other personnel in the future. Some industry experts have argued for redirecting physician activity in a way that will focus on outcomes.

Three Steps Health Care Organizations Should Take to Reinvest in their Physicians

What should health care organizations do to maintain the strength and relevance of their physician workforce? Start by accepting the reality that health care is on a trajectory away from fee-for-service, and, therefore, it’s time to begin measurement of quality and cost performance, as well as the patient experience, in earnest.

- Redefine the measures of productivity and value. Providers should see quality measures and comparisons with their peers on outcomes over time, as well as by risk-adjusted patient panel volume and process measures.

- Build time and process for physician-patient discussion and shared decision-making. Patients will make decisions in the future, and an organization should make a valiant attempt to keep those patients in-network. Without a dedicated process and training about how to talk to patients in the current environment, those patients will make fast tracks to another provider who can do better.

- Build a care team and construct its roles and responsibility around new consumer attitudes and behavior. For many large health care organizations, this could mean a major overhaul of everything from medical records to patient scheduling and services.

Time is short, and revenues are sliding quickly. Responding to the national debate, many states are engineering state-wide initiatives for health coverage and redesigning the care system. Physicians and health care organizations will need to modify their own operations soon, lest they wake up to discover that their roles have become marginalized under financial risk, VBHC or state-wide initiatives.

Founded as ICLOPS in 2002, Roji Health Intelligence guides health care systems, providers and patients on the path to better health through Solutions that help providers improve their value and succeed in Risk. Roji Health Intelligence is a CMS Qualified Clinical Data Registry.

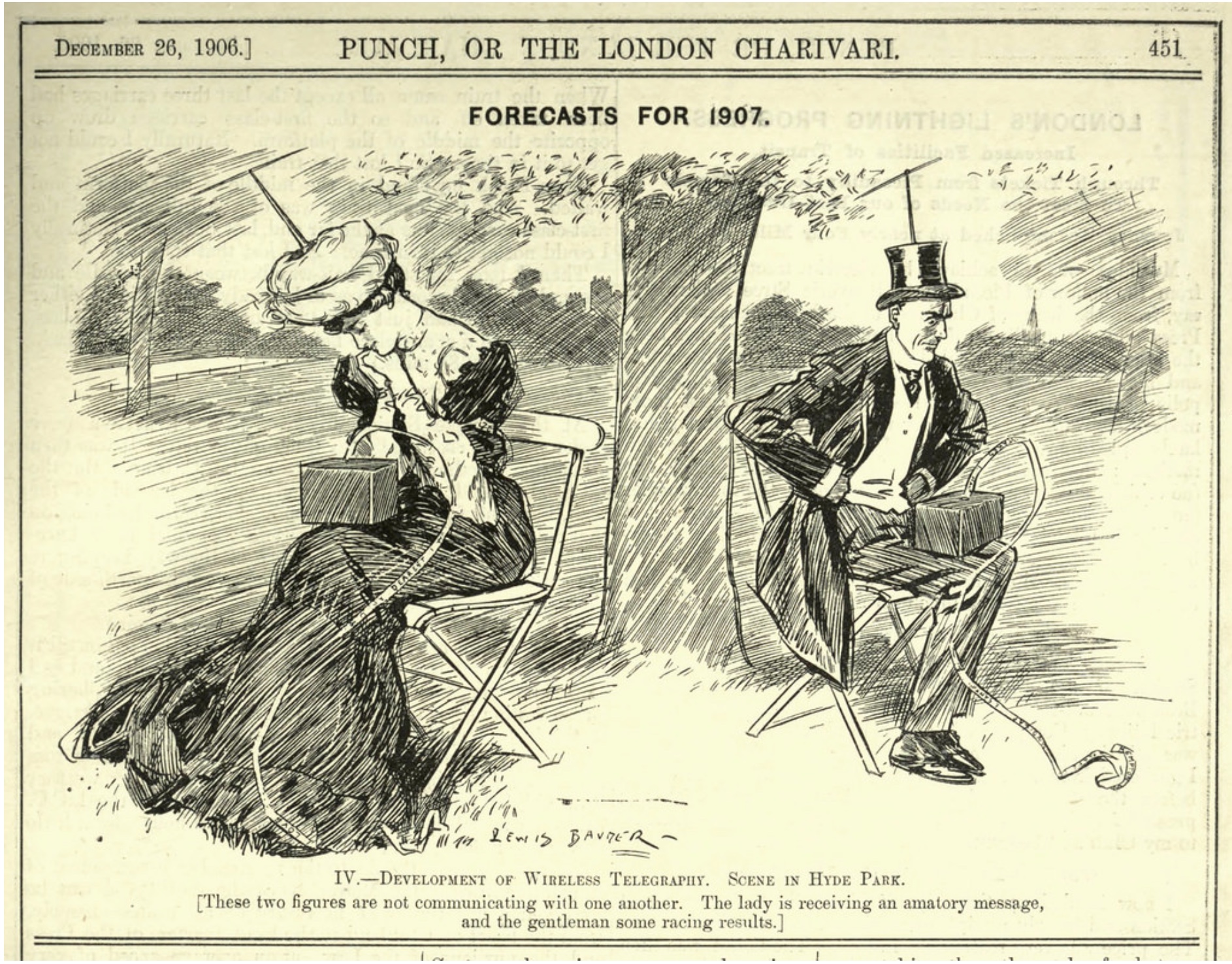

Image Credit: Punch, December 26, 1906, “Forecasts for 1907.” Public Domain Review.